Ever found yourself scrolling through endless tables of gemstone facts, wondering "where is garnet found" and hoping the answer feels less like a geography lesson and more like a story you can actually use?

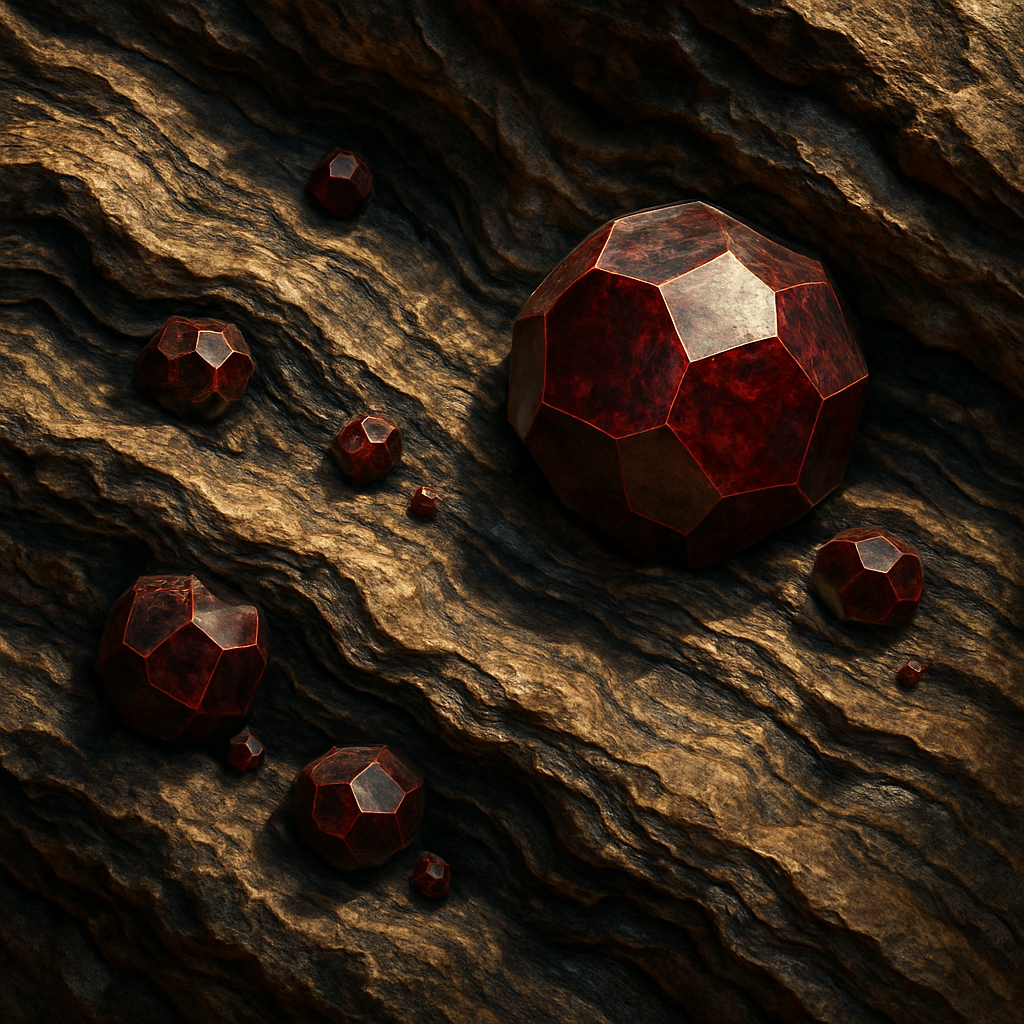

You're not alone. Garnet is one of those colour‑rich stones that pops up in everything from medieval jewellery to modern beading kits, yet its origins are scattered across the globe. The most famous deposits sit in the deep reds of the Indian state of Rajasthan, the fiery hills of Brazil's Minas Gerais, and the ancient mining tunnels of South Africa’s Limpopo Province. Each region gives the stone its own subtle character – the Indian almandine tends to be a deep, almost blood‑red, while Brazilian pyrope can sparkle with a slightly brighter hue.

But there's a hidden gem (pun intended) that many crafters overlook: Mozambique. In recent years, this East African coastline has become a top source for high‑quality dark red garnet, prized for its uniform colour and excellent clarity. The mineral‑rich soils there produce beads that feel smooth in the hand and hold colour even after years of wear.

If you're planning a new collection or just love adding a pop of passionate red to a necklace, sourcing authentic stones matters. At Charming Beads we stock a strand of dark red garnet beads sourced from Mozambique, ethically mined and ready to string onto your next design. Knowing the exact origin helps you speak confidently about the piece’s story – and your customers love that personal touch.

So, why does the birthplace of a gemstone affect your work? Because the geology influences everything from colour saturation to hardness, and that in turn dictates how the bead behaves when you set it in metal or polish it for a pendant.

Stick with us and we'll walk you through the major garnet locales, the myths that grew around them, and practical tips on choosing the right variety for your next project. Ready to dive deeper?

TL;DR

Garnet shows up worldwide – from India’s deep almandine veins and Brazil’s bright pyrope hills to Mozambique’s smooth dark‑red chips and South Africa’s historic mines, each source giving the stone its distinct hue and hardness.

That knowledge lets you choose the right beads, share a genuine story, and source ethically confidently.

Geological Formation of Garnet Deposits

Ever wondered where is garnet found deep underground, not just sparkling in a jewellery shop?

Let’s pull back the curtain and look at the rock‑stuff that cooks up these brilliant stones.

Metamorphic roots

Most garnet crystals are born in the pressure cooker of metamorphism.

When a shale‑rich sedimentary layer is slammed between converging tectonic plates, heat and pressure break old bonds and let new minerals recrystallise.

In that hot, dense environment aluminium‑rich minerals combine with iron, magnesium or manganese to form the six classic garnet varieties – almandine, pyrope, spessartine, and so on.

According to Geoscience Australia, “most garnet forms when a sedimentary rock with high aluminium content, such as shale, is metamorphosed,” a process that commonly occurs at convergent plate boundaries.

So, why does this matter to you? The same pressure that creates garnet also aligns its crystal lattice, giving the stone its famed hardness (7‑7.5 on the Mohs scale) and durability for jewellery or industrial use.

Igneous intrusions and volcanic settings

Not all garnet comes from metamorphic blankets.

Some varieties crystallise from cooling magma.

In granite or basaltic bodies, the melt is rich in the right chemistry and, as it solidifies, garnet can grow as large, gem‑quality crystals.

For example, the famous pyrope‑rich “Garnet Trail” in Connecticut shows garnet nestled within granitic pegmatites, a testament to igneous‑related formation.

If you’re picturing a slow‑cooking stew, think instead of magma flashing into rock in minutes to hours – a rapid but still ordered dance of atoms.

Does this rapid cooling give you a different colour palette? Yes – igneous garnets often display vivid reds and greens, while metamorphic ones can be more muted or mixed.

From rock to sand – how garnet travels

Once formed, garnet doesn’t always stay locked in bedrock.

Over millions of years, weathering peels away softer minerals, leaving the toughest grains behind.

These dense grains roll downstream, collecting in riverbeds and eventually in ancient sand dunes.

The iconic Port Gregory deposit in Western Australia, for instance, is a massive “garnet sand” field where ancient streams concentrated the hardest minerals into dunes that we now mine for industrial abrasives.

That same process explains why you can find garnet in alluvial gravels across the globe – from the Harts Ranges in the Northern Territory to the river terraces of the Czech Republic.

Want to see garnet in action? Check out the video below where a water‑jet cutter slices steel using garnet‑sized particles – a perfect illustration of how nature’s hardest grains power modern tools.

When you’re sourcing beads for your next project, remember the journey they’ve taken.

Our dark red garnet beads are harvested from those very ancient sand deposits, giving you a piece of Earth’s high‑pressure history in every strand.

Finally, a quick note from the research side: the comprehensive CT Garnet Trail document details the mineral‑paragenesis and confirms that garnet stability is tied to specific pressure‑temperature windows (CT state report).

So the next time you hold a garnet bead, think of the mountain‑crushing forces, the slow river rides, and the centuries of geological storytelling that made that flash of colour possible.

Enjoy exploring these hidden treasures!

Major Global Locations Where Garnet Is Found

When you start asking "where is garnet found", the answer sprawls across continents like a colourful map drawn by nature itself. You’ll soon discover that each region leaves a tiny fingerprint on the stone – a hue, a clarity, even a story you can share with a client.

India’s Rajasthan – the classic almandine mines

Rajasthan’s arid hills have been yielding deep‑red almandine for centuries. The mines near the town of Udaipur sit on high‑grade metamorphic belts where pressure and heat have squeezed iron‑rich garnet crystals into a vivid, almost blood‑red colour. Because the crystals grow slowly, they often exhibit a glassy luster that jewellery designers love.

Actionable tip: ask your supplier for a provenance sheet that mentions "Rajasthan almandine" – it reassures customers that the beads carry an authentic Indian legacy.

Brazil’s Minas Gerais – bright pyrope and spessartine

Head south to Brazil and you’ll hit the famed Minas Gerais province. Here the volcanic‑derived rocks have birthed pyrope garnets that glow with a raspberry‑pink brilliance, and spessartine that leans toward orange‑red. The region’s open‑pit operations make bulk‑sized grains ideal for industrial abrasives as well as large bead strands.

Practical step: when buying in bulk, weigh a sample against a known Brazil‑origin stone; the density differences are subtle but measurable.

Mozambique’s coastal belt – smooth dark‑red gems

If you’ve ever held a strand of dark‑red garnet that feels almost buttery, chances are it came from the East African coastline of Mozambique. Recent mining concessions have focused on alluvial deposits where ancient river systems concentrated the hardest grains. The result is a uniform colour and a clean, rounded shape that threads beautifully on a necklace.

Quick check: genuine Mozambique garnet rarely shows the gritty inclusions common in older Indian deposits – a visual cue you can use during quality control.

South Africa’s Limpopo Province – historic underground veins

Limpopo offers a more rugged profile. The underground veins there produce almandine with a slightly darker tone and occasional greenish hints, a sign of manganese admixture. These stones have been mined by small‑scale cooperatives for generations, giving them a strong ethical story.

Action: request a small video of the mining site or a certificate of fair‑trade compliance to back up your marketing claims.

Australia – Harts Ranges and Western Australia’s garnet sand

Down under, the Harts Ranges in the Northern Territory host metamorphic garnet that’s prized for its hardness – perfect for industrial grinding media. Meanwhile, the massive “garnet sand” fields of Western Australia’s Port Gregory deposit provide a ready supply of sand‑sized grains used in water‑jet cutting.

Tip for crafters: if you need tiny, uniform beads for a delicate beaded bracelet, ask for “Port Gregory sand‑grade garnet” – the grains are naturally rounded and size‑sorted by nature.

North America – Connecticut’s Garnet Trail and North Carolina

In the United States, the Garnet Trail of Connecticut showcases garnet that grew inside granitic pegmatites. These crystals are often larger and clearer, making them a favourite for high‑end jewellery pieces. Further south, North Carolina’s “Gold Hill” area yields almandine that carries a warm, earthy red, ideal for rustic designs.

How to verify: compare the crystal habit – Connecticut garnets are commonly octahedral, whereas North Carolina stones are more irregular.

Europe – Czech Republic and Norway

Central Europe isn’t left out. The Czech Republic’s Bohemian Massif supplies garnet that’s been used in traditional folk jewellery for centuries. In Norway, garnet occurs in the Skagerrak area, often as tiny, dark grains that make excellent polishing compounds.

Pro tip: European garnet often carries a subtle “smoky” undertone – a visual cue you can highlight when writing product descriptions.

Putting it all together for your next collection

Now that you’ve toured the world’s major garnet hotspots, you can match the stone’s origin to the story you want to tell. Whether you need the deep drama of Rajasthan almandine, the vibrant pop of Brazilian pyrope, or the smooth consistency of Mozambique dark‑red, the source defines the narrative.

To see a curated selection that spans these regions, explore our full range of garnet beads by material and filter by colour or origin. From there you can build a collection that feels both global and personal.

Finally, remember to document the origin on every product label – it builds trust, fuels SEO with the keyword "where is garnet found", and gives your customers a tangible piece of planetary history to hold in their hands.

Types of Garnet and Their Typical Localities

When you ask yourself “where is garnet found”, the answer isn’t a single dot on a map – it’s a whole palette of mineral families, each with its own favourite neighbourhood.

Almandine – the classic deep‑red

Almandine is the iron‑rich star of the garnet world. You’ll mostly meet it in metamorphic schists and gneisses across the Indian subcontinent, especially the rugged hills of Rajasthan. Those same conditions also give us the dark‑red almandine from the historic mines of North Carolina and the high‑grade veins of the Adirondacks in New York.

For crafters, almandine’s strong colour and good hardness make it a reliable choice for bold beaded necklaces that need to stand the test of time.

Pyrope – fire‑like and often found in volcanic rocks

Pyrope loves the heat of igneous settings. In Brazil’s Minas Gerais, the volcanic‑derived pegmatites produce pyrope with a raspberry‑pink glow that’s instantly recognisable. Look further afield to the mantle‑derived peridotites of South Africa’s Limpopo Province – there you’ll also find pyrope that’s a shade darker, perfect for a subtle, sophisticated finish.

If you want a pop of colour that catches the light, a strand of Brazilian pyrope will do the trick.

Spessartine – manganese‑rich orange‑red

Spessartine’s manganese gives it a warm orange‑red hue you often see in skarn deposits. Madagascar’s eastern skarns are world‑renowned for this variety, but you’ll also meet spessartine in the granitic pegmatites of the Czech Republic and in some low‑grade metamorphic rocks of the United States.

Because it’s slightly softer than almandine, spessartine works beautifully in jewellery that’s meant to be worn close to the skin, where a gentle polish can enhance its glow.

Grossular – the greenish‑yellow family

Grossular covers a range of colours from clear yellow to vivid green. The green “tsavorite” form hails from the Tsavo region of Kenya and the neighbouring Tanzanian highlands. In Europe, you’ll find the yellow‑brown “cinnamon stone” in the Alpine skarns of Austria and Italy.

Its relatively high refractive index makes grossular a favourite for pendant settings that need a little extra sparkle.

Andradite – a versatile calcium‑iron variety

Andradite shows up in many shades – from the deep black of melanite to the bright yellow of topazolite. Classic localities include the skarns of Norway’s Skagerrak area and the calcium‑rich limestones of the Ural Mountains in Russia. In the United States, small pockets appear in the metamorphic belts of North Carolina.

Designers love the darker forms for a gothic aesthetic, while the yellow tones add a sunny accent to summer collections.

Uvarovite – the rare green jewel

Uvarovite is the only naturally green garnet most of us ever see. It’s a calcium‑chromium species that crops up in the chromite‑rich ultramafic rocks of the Ural Mountains, Finland’s Outokumpu region, and occasionally in South Africa’s mantle‑derived kimberlite pipes.

Because it’s so scarce, a few uvarovite beads can become the signature piece of a high‑end line – just make sure you highlight the exotic origin.

Putting the pieces together

Now that you know the main types and where they tend to grow, you can match the stone to the story you want to tell. A deep‑red almandine from Rajasthan whispers of ancient caravans, while a bright pyrope from Brazil shouts modern vibrancy.

Remember, the mineral’s chemistry also dictates its hardness and how it behaves in your designs – a practical detail that can save you headaches later on.

For a quick reference, the garnet family overview on Wikipedia breaks down the pyralspite and ugrandite series and lists the classic localities for each species.

So, next time a client asks “where is garnet found”, you can answer with confidence, colour, and a little bit of wanderlust.

How to Identify Garnet in the Field

Ever found a flash of deep red or orange in a river gravels and wondered, "where is garnet found"? You're not alone. Spotting garnet on a dig is part science, part intuition, and a little bit of luck.

Let’s walk through a practical checklist you can carry in your pocket, whether you’re hunting in the Harts Ranges or just skimming a beach in Alaska.

1. Trust the colour, but don’t be fooled

Garnets love rich reds, but they also show up in orange‑brown, deep green, yellow and even pink. The classic almandine will look almost blood‑red, while spessartine leans toward a warm orange‑red. If you see a stone that’s a uniform, glassy red with no obvious inclusions, you’re probably on the right track.

Keep an eye on subtle hints – a slight brownish rim can signal a metamorphic origin, whereas a brighter raspberry hue often points to an igneous source like Brazil’s pyrope.

2. Test the hardness on the spot

Garnet sits between 6.5 and 7.5 on the Mohs scale. A quick scratch test with a steel nail (hardness ~5.5) should leave a faint mark on most rocks, but the garnet itself will resist. If the stone chips cleanly or leaves a powdery residue, you’re likely dealing with something softer, like quartz.

Remember, a hard‑knocking feel in your hand is a good first clue – garnet is tough enough to survive a tumble in a river for centuries.

3. Look for the tell‑tale crystal habit

In the field, garnet often appears as dodecahedral or octahedral grains. When you spot a tiny, well‑formed “double‑pointed” crystal, pause – that geometry is a hallmark of garnet growing under pressure.

Even if the stone is rounded by water action, the edges tend to stay slightly angular, unlike the smoother, more rounded quartz grains.

4. Check specific gravity with a simple float test

Garnet is denser than most common silicates. Drop a piece into a small jar of water; if it sinks quickly, you’ve got a heavy mineral on your hands. A quick comparison with a known quartz grain (which floats or sinks slowly) can confirm the density difference.

For a rough estimate, a garnet grain will feel noticeably heavier when you hold it between thumb and forefinger.

5. Take note of the surrounding matrix

Where the stone lives can tell you a lot. Metamorphic schists and gneisses often host almandine, while granite pegmatites are the playground of spessartine and pyrope. If you’re sifting through alluvial sand, think about the upstream source – a river that cuts through an old metamorphic belt is a strong hint.

In coastal deposits like Mozambique’s sand‑grade garnet, you’ll see rounded grains that have been tumbling in the surf for ages.

6. Use a field guide for quick reference

Having a pocket‑size mineral guide can save you endless guesswork. According to a field guide on garnet, the combination of colour, hardness, and crystal form narrows the identification down to a handful of species.

Keep the guide open to the garnet page and compare your specimen side‑by‑side with the illustrated examples.

7. Document and verify

Snap a photo, note the GPS location, and write down the colour, hardness feel and any visible crystal faces. When you get back to the workshop, a quick lab test or a jeweller’s loupe can confirm your field impression.

And if you’re sourcing beads for a design, that provenance note becomes a selling point – your customers love a story that says exactly where the stone was found.

So, next time you’re out with a trowel or a simple hand‑screen, run through this checklist. Within a few minutes you’ll know if you’ve just uncovered a piece of Earth’s high‑pressure history, ready to become the star of your next jewellery collection.

Economic Importance and Mining Practices for Garnet

Why does garnet matter beyond pretty jewelry?

When you think of garnet, the first image that pops up is probably a deep‑red pendant. But the truth is, garnet fuels whole industries that you might never see.

From blasting rock in a quarry to polishing a smartphone screen, this mineral’s hardness and density make it a workhorse in manufacturing.

So, what does that mean for you as a crafter or a supplier?

Industrial heavy‑hitters

Garnet’s 6.5–7.5 on the Mohs scale puts it right up there with quartz and topaz. That’s why it’s the go‑to abrasive for water‑jet cutting, sand‑blasting, and grinding.

In fact, the global garnet abrasive market is worth billions, with demand driven by aerospace, automotive, and construction sectors.

And because garnet is chemically inert, it won’t corrode equipment – a huge cost saver over time.

Jewelry and the gemstone trade

Don’t overlook the gemstone side. High‑quality almandine, pyrope, and spessartine fetch premium prices, especially when sourced from renowned locales like Rajasthan, Brazil’s Minas Gerais, or Mozambique’s coastal deposits.

Designers love garnet for its rich colour palette, and collectors pay top dollar for stones with good clarity and cut.

That dual market – industrial and decorative – gives garnet a unique economic resilience.

Where does the mineral come from?

Most commercial garnet is mined from metamorphic schists and gneisses, but alluvial “garnet sand” is also a big player.

In Western Australia’s Port Gregory, ancient riverbeds have concentrated the hardest grains into a beach‑wide resource that’s trucked straight to abrasive plants.

In the United States, the Appalachian belt and the Adirondacks host vein‑type deposits that are mined via open‑pit or underground methods.

Mining methods at a glance

- Open‑pit mining: Large‑scale excavators scoop out garnet‑rich rock, which is then crushed and screened.

- Underground mining: Used for high‑grade veins where surface disturbance must be minimised.

- Alluvial dredging: A gentler approach that washes river‑bed sediments through sieves to separate dense garnet grains.

- Heavy‑media separation: After crushing, a slurry of water and iron filings pulls the heavier garnet out of the lighter gangue.

Each technique balances cost, ore grade, and environmental impact. Open‑pit is cheapest but leaves a bigger footprint; dredging is eco‑friendlier but yields lower concentrations.

Processing tips for maximum value

Once you have the raw concentrate, the next step is sizing. Garnet used for abrasives is typically 0.5–1 mm, while gemstone cuts start at 2 mm and up.

Magnetic separation removes iron impurities, and flotation can further polish the grain surface – a crucial step for high‑precision cutting tools.

Remember: a clean, uniformly sized batch commands a premium price, whether you’re selling to a grinding‑wheel manufacturer or a jeweller.

Environmental and regulatory notes

Modern mining operations are under strict scrutiny. Re‑vegetation, water‑recycling, and tailings management are now standard requirements.

Many producers now adopt “closed‑loop” processing plants where water is filtered and reused, cutting both costs and carbon footprints.

Staying ahead of regulations not only avoids fines – it also appeals to eco‑conscious buyers who are willing to pay more for responsibly sourced garnet.

Bottom line: profit from versatility

Whether you’re eyeing the abrasive market, the gemstone trade, or both, garnet offers a diversified revenue stream.

Understanding the mining method that best suits your deposit – open‑pit, underground, or alluvial – can dramatically affect your margins.

And don’t forget the processing stage: clean, well‑sorted garnet fetches the highest prices across all end‑uses.

For a deep dive into the geology, mining techniques, and economic impact of garnet, check out the detailed USGS analysis of garnet deposits and their uses. It’s the go‑to reference for anyone serious about turning this ruby‑red rock into profit.

Comparison of Garnet Quality by Major Mining Regions

When you ask yourself “where is garnet found”, the answer isn’t just a dot on a map – it’s a story about colour, clarity and how the stone behaves in your designs.

Let’s take a quick stroll through the world’s biggest producers and see how the local geology tweaks the final bead.

Rajasthan, India – deep‑red almandine

In the arid hills of Rajasthan the garnet grows in high‑grade metamorphic schists. The pressure‑heat combo squeezes iron into the crystal, giving a dark, almost blood‑red hue and a glassy luster.

Because the crystals form slowly, they often show clean faces and fewer inclusions – perfect for statement necklaces that need that rich, dramatic punch.

Minas Gerais, Brazil – bright pyrope and spessartine

Brazil’s volcanic pegmatites produce a brighter palette – raspberry‑pink pyrope and orange‑red spessartine. The rapid cooling leaves a slightly more porous structure, which can make the stones a tad softer but gives them a lively sparkle.

Designers love the colour intensity for summer collections, even if they need a little extra polishing to reach a high gloss.

Port Gregory, Western Australia – sand‑grade industrial garnet

The massive “garnet sand” fields here are the result of ancient rivers concentrating the hardest grains. The grains are naturally rounded, uniform in size and extremely dense.

That uniformity means they’re the go‑to for abrasive media, but they also make tiny, perfectly round beads for delicate jewellery that slides onto a thread without snagging.

Garnet Hill, Nevada, USA – mixed‑quality alluvial garnet

At Garnet Hill you’ll find garnets washed out of rhyolite outcrops into the drainage. They’re often smaller and more varied in colour, ranging from deep red to brownish‑orange. While many aren’t gem‑grade, the sheer volume gives a reliable supply for bulk abrasive use.According to the BLM site, the area is a favourite spot for rock‑hounds hunting these semi‑precious gems.

For crafters, the hill can still produce occasional gems that, when sorted, add a rustic charm to a mixed‑material necklace.

South Africa’s Limpopo – dark almandine with greenish hints

Underground veins in Limpopo host almandine that carries a subtle greenish tint, a sign of manganese admixture. The stones tend to be medium‑sized and have a slightly rougher surface because they haven’t been water‑rounded.

That texture can be an advantage for a textured bead look – you don’t have to sand them down yourself.

What does this mean for your next project?

Think of the region as a flavour profile. If you need a deep, dramatic colour with minimal inclusions, reach for Rajasthan almandine. If you want a vivid pop that catches the light, Brazil’s pyrope is your mate. Need ultra‑uniform beads for a fine‑wire design? Western Australia’s sand‑grade grains are the answer. And when you’re on a budget but still want authentic garnet, the mixed batch from Nevada can add character without breaking the bank.

Here’s a quick cheat‑sheet to help you decide which source fits your design brief.

| Region | Typical Colour/Clarity | Best Use |

|---|---|---|

| Rajasthan, India | Deep blood‑red, high clarity | Statement jewellery, premium beads |

| Minas Gerais, Brazil | Raspberry‑pink / orange‑red, lively sparkle | Colour‑focused designs, summer pieces |

| Port Gregory, Australia | Uniform red, rounded grains | Industrial abrasives & tiny uniform beads |

So, when you’re scrolling through supplier catalogues, ask yourself: does the origin match the story I want to tell? A little geology knowledge can turn a simple bead into a selling point that resonates with your customers.

Next step? Grab a few samples from each region, compare the colour and feel, and let the story guide your next collection.

Conclusion

We've taken a quick trip from the deep‑red veins of Rajasthan to the bright pyrope hills of Brazil, and even the smooth dark‑red chips that roll out of Mozambique's coastal sands.

So, where is garnet found? In short, wherever the earth has squeezed pressure and heat into iron‑rich minerals – from metamorphic schists in India to alluvial sand‑grades in Western Australia, and from volcanic pegmatites in South America, and historic underground veins in South Africa.

What does that mean for you, the jewellery maker? The origin you choose instantly shapes the colour story, the hardness you can rely on, and the narrative you can share with a client.

Next time you browse a bead catalogue, pause and ask yourself: does this stone’s birthplace match the emotion I want my piece to evoke? A Rajasthan almandine whispers ancient caravans, while a Mozambican dark‑red feels like a quiet sunrise on the Indian Ocean.

Take a moment now to pull a few samples, compare the hue, the feel, and let the geology guide your next collection. When you’re ready, let Charming Beads help you source ethically‑sourced garnet that tells a genuine story.

Remember, a well‑chosen garnet not only adds colour but also boosts the perceived value of your design – a small detail that can make a big difference.

FAQ

Where is garnet found around the globe?

Garnet pops up on every continent where heat and pressure have squeezed iron‑rich minerals together. Think the deep‑red almandine veins of Rajasthan, the raspberry‑pink pyrope hills of Brazil’s Minas Gerais, the smooth dark‑red chips washed up on Mozambique’s coast, and the massive sand‑grade deposits at Port Gregory in Western Australia. Even the United States has pockets – Connecticut’s pegmatite trail and North Carolina’s historic mines. Each locale leaves a subtle fingerprint on the stone’s colour and clarity.

Can I guess a garnet’s origin just by its colour?

Colour is a helpful clue, but it isn’t a guaranteed GPS. A deep, blood‑red hue often points to Indian almandine, while a bright raspberry‑pink usually means Brazilian pyrope. Dark, uniform reds are common from Mozambique’s alluvial sands, and a slightly greenish tint can hint at South African limestone‑derived almandine. Pair colour with texture, crystal habit and density for a more confident guess.

Is Brazilian garnet really different from Indian garnet?

Yes, the geology shapes the stone. Brazilian garnets grow in volcanic pegmatites, giving them a slightly more porous structure and a vivid sparkle that can appear a touch softer on the Mohs scale. Indian garnets, forged in metamorphic schists, tend to be denser, clearer, and boast a glassy luster that holds up well under heavy wear. Those differences can influence which variety suits a bold necklace versus a delicate bracelet.

How does the mining method affect the quality of garnet beads?

Open‑pit mining yields large, rough crystals that are often trimmed and polished for jewellery, while alluvial dredging produces naturally rounded grains that thread easily and feel uniform on a string. Underground veins can give you irregular shapes but sometimes higher clarity because the stones haven’t been tumbling in rivers. Knowing the extraction style helps you pick beads that match the finish you need – smooth and uniform or rugged and character‑rich.

Are there ethical concerns I should watch for when sourcing garnet?

Absolutely. Some regions have lax labour standards or minimal environmental safeguards. Look for suppliers who provide provenance sheets, fair‑trade certifications, or evidence of reclamation programmes. Small‑scale cooperatives in South Africa and responsibly managed mines in Brazil often publish their sustainability policies. When you can verify that the garnet was extracted with minimal ecological impact, you not only protect the planet but also add a compelling story to your pieces.

What should I check before buying garnet beads for my designs?

First, feel the weight – genuine garnet is noticeably heavy for its size. Next, examine the surface: a glassy sheen without excessive inclusions usually signals higher quality. Verify the colour matches the origin you want to convey; a uniform hue is easier to mix in a design. Finally, ask for a small batch sample or a certification of origin – it builds trust with your customers and protects you from counterfeit stones.

How can I care for garnet jewellery so the colour stays vibrant?

Garnet is tough, but it still appreciates gentle handling. Clean beads with a soft, damp cloth and mild soap; avoid ultrasonic cleaners that might loosen any fragile settings. Store pieces separately in a padded pouch to prevent scratching against harder gemstones. If a bead looks dull, a quick polish with a jeweller’s cloth restores its natural sparkle. Regular care keeps the stone’s colour as vivid as the day you first sourced it.